Strip Poachers: Fandom & Appropriation in Neo-Burlesque.

~ Written by Sailor St. Claire, Special Guest Contributor

JoJo Stilleto has dubbed summer 2012 the “Summer of Nerdlesque” and documented several instances of nerdlesque (or geeklesque, if you prefer) performances in our fair city for this very site. If you happen to spend a lot of your life traveling through wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey stuff, or don’t get out much due to your duties as a Slayer, here’s a quick definition of nerdlesque as a performance genre: nerdlesque is a means for fans to perform loving tributes to their favorite pop culture properties. It’s getting your geek on while taking your clothes off. But although nerdlesque is clearly a trend in our community, I’d like to propose that nearly all neo-burlesque is, in a way, nerdlesque.

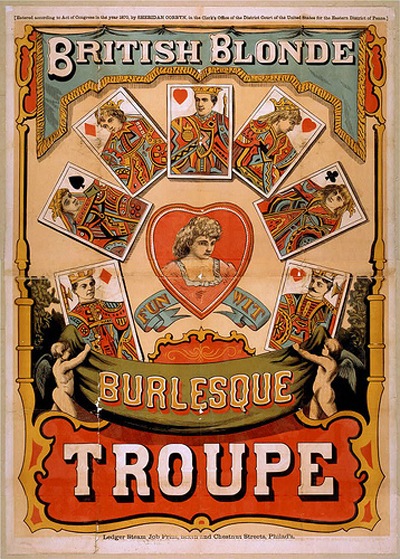

What I mean is that burlesque is and always was a kind of fan culture. Classical burlesque, the burlesque genre Lydia Thompson and her British Blondes brought to the United States in 1869, was a style of performance in which women in drag performed parodies of classical dramas. These scripts poked fun at contemporary culture from within their ancient narrative contexts by including political satire, cultural references to other popular entertainments of the time, and so on. The racy part of these performances was the costuming: burlesque actresses performing male roles wore breeches that showed the curves of their calves and ankles through silk socks. The appearance of feminine calves in a masculine role was yet another way performers poked fun at contemporary culture: by asserting a visual gag about gender into the genre of the performance itself. The texts they performed drew extensively on mainstream popular culture in the late 19th century, appropriated it, poked fun at it, and, in so doing, extended the text’s life and meaning in a way that enabled burlesque performers (and writers) to articulate something about the culture in which they were performing.

This method of appropriating, rescripting, and extending texts is what media studies scholar Henry Jenkins refers to as “textual poaching.” For Jenkins, poaching is the very heart of fan culture. Fandom, and particularly fan fiction, filk songs, or other kinds of fan-art that is sourced and created by fan communities, is about arresting control of the dominant text from its creator to rework it for one’s own purposes. So if Mulder and Scully don’t hook up onscreen, they can hook up in fan fiction (or, if you prefer, Mulder can hook up with Krychek). When fans create content that extends the fannish universes of their choosing, fans then have control over the creation of the dominant narrative. Likewise, a burlesque number such as Scarlett O’Hairdye’s “Romana” act (in which she considers what Romana would do with the 4th Doctor’s scarf if she were alone with it in a Tardis) appropriates the Whoniverse and extends the narrative in the manner of the performer’s imagining. Nerdlesque can also appropriate and resignify the meaning of the texts they poach, as I do in my “Trouble with Tribbles” number. Those problematically multiplying, purring little balls of fur from the classic Star Trek episode become my pasties and merkin. It’s a parodic appropriation and resignification of a dominant cultural text which turns a sci-fi icon into a comment on body hair.

The union of burlesque and fandom that is the nerdlesque movement marks an important feminist intervention with fan culture, a topic I spoke about at the inaugural GeekGirlCon in 2011. The nerdlesque genre and GeekGirlCon share similar missions: to create a female-driven space through which women can celebrate their geekery without being subject to (and objectified by) fandom’s patriarchal tendencies. In Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura Mulvey argues that the eye of the camera replicates the male gaze, particularly noticeable in cinema’s tendency to represent female bodies as fragmented accumulations of parts (legs, breasts, lips, eyes, hair) rather than whole figures. This fragmentation stalls the body’s potential for action. It renders something as progressive as a superheroine into a passive object of the male gaze. Because science fiction fandoms have been historically created by and for men, these kinds of fragmented representations of female bodies tend to persist within fan culture. Fanboys get upset at the thought of Wonder Woman donning pants (that are still skin tight), while fangirls are saddened to see Starfire wearing the comic book equivalent of a Slingshot. (Not that Slingshots aren’t awesome – they’re just not awesome on teenage girls.) Then there are booth babes: the models hired by film studios, game designers and comic houses to dress up as female characters from fan universes in order to pose for pictures and sell merchandise. The booth babe has very little agency. She’s the opposite of the empowered heroine she may be dressed up to represent. And the ratio of male to female characters within fannish universes is still skewed in favor of those with Y-chromosomes.

Although these fannish universes might exhibit very masculinist tendencies, most fan fiction (particularly slash fiction) is written by women. Because fan fictions are about arresting control of the dominant narratives from their creators to extend the possibilities of the text, this creative aspect of fandom is a space where women can have agency. As the neo-burlesque movement is built on the foundations of feminist performance art, it too grants agency to its participants. Unlike the booth babes (or the sci-fi heroines they dress up as), burlesque allows the performer to control the gaze of the audience. Every movement of a hand, every well-placed glance, is intended to guide where the audience is meant to look. By inviting and manipulating the gaze, the performer retains agency through action. This is a common feature in all neo-burlesque. It allows performers to narrate their own bodies while telling stories – even if those narratives are poached from other sources.

Though not all neo-burlesque is nerdlesque, it seems to return to the model begun by Lydia Thompson in its need to poach from cultural texts. Neo-burlesque draws inspiration from pop music (Valkyrie Production’s Women Behind the Music), movies and television (Roxy Ruby & Pepper Patootie’s Blues Brothers duet, “Mission from Gawd”), and politics (The Von Foxies’s “Masochism Tango”). While not necessarily derived from “fannish” universes, performances that reference contemporary culture are, in a sense, poaching from dominant cultural texts and rescripting them. In this way, all neo-burlesque shares a common desire for the creation and control of meaning, whether that is about how female bodies should be looked at through manipulation of the audience’s gaze or about the co-option of a pre-existing cultural narrative.

But to say that the brunt of meaning making lies entirely with the performer would neglect a key part of burlesque as a genre. Neo-burlesque is a special kind of live theatre that invites audiences to share more intimate connections with performers via the lack of a fourth wall and the potential for interaction. In fact, the participation of the audience in the forms of hoots, hollers, cheers and other forms of call-and-response add another layer to the struggle for meaning. So when Iva Handfull locks eyes with you during her dirty cowpoke strut (“Marlboro Woman”), your response is actually reshaping the narrative arc of the act. It matters whether or not you meet Iva’s gaze or look away. And it matters where you cheer and what you cheer for. So burlesque fans, too, co-opt authorship by inserting their own voices and actions into the performer’s narrative. Another unique feature in burlesque is the way in which performances are built around the need for this audience response, and thus invite it in. This recognizes the need for meaning to be a co-constructive act between audiences and performers, fans and creators – which is why nerdlesque is very much at home within the larger world of neo-burlesque.

***

Sailor St. Claire isn’t called The Showgirl Scholar for nothing. In addition to stripping off sparkly bits, she’s working on her doctorate in English literature and routinely returns graded papers to her students that are covered in glitter. She is a member of Tempting Tarts Burlesque and the producer of Tuesday Tease, a monthly burlesque revue with live musical accompaniment at Lucid Jazz Lounge.

[…] it, transforming it, and rewriting it through a different genre, it gets to be alive again. (See my Burlesque Seattle Press article from last summer for further thoughts on burlesque and textual poaching.) We get to go back to Hogwarts, we get to […]

Burlesque = Magic: Sailor St. Claire on Accio Burlesque. | Burlesque Seattle Press said this on 06/23/2013 at 4:25 pm |